Just like us, pigs, sheep and cows excrete what they are unable to digest. Besides unpleasant smells, this also creates huge problems for the environment. The project that has now been given the green light aims to get a handle on these problems and make livestock farming cleaner.

Storing animal excrement releases methane, ammonia, nitrous oxide and various aerosols, among other substances. And these emissions are anything but harmless: the pungent-smelling gas ammonia, for instance, is toxic at elevated concentrations and can contribute to eutrophication. It is regarded as particularly dangerous if it transforms into nitrous oxide, which is a greenhouse gas that is harmful to the climate. As a general principle, these emissions act like a sheet of window glass in the atmosphere, preventing heat from the Earth’s surface from radiating out into space. Nitrous oxide is 300 times as effective at this as carbon dioxide is, making it a kind of invisible double glazing. Livestock farming releases even larger quantities of methane, which is 28 times worse for the climate than carbon dioxide.

Do the methods do what they claim to?

Reducing the amount of gas emitted is thus an important objective on the path to improved climate and environmental protection. “There are now a whole host of methods that can do this, at least under lab conditions,” explains Prof. Dr. Wolfgang Büscher from the Institute of Agricultural Engineering at the University of Bonn. “But it’s often hard to assess whether these results are transferable to the kind of scale you get in real life.”

This is partly because producing accurate measurements for a livestock farm’s emissions is a very laborious, time-consuming and expensive process, with the measuring equipment alone often costing hundreds of thousands of euros. Plus there is the fact that measurements should be taken in different weather conditions, ideally on multiple occasions at different times of year. When it comes to ways to reduce emissions, just taking measurements from a single farm is not sufficient either. “You need several years on average to get a sound idea of how successful a measure is,” stresses Dr. Manfred Trimborn from the Institute of Agricultural Engineering.

Bringing AI into sheds and stalls

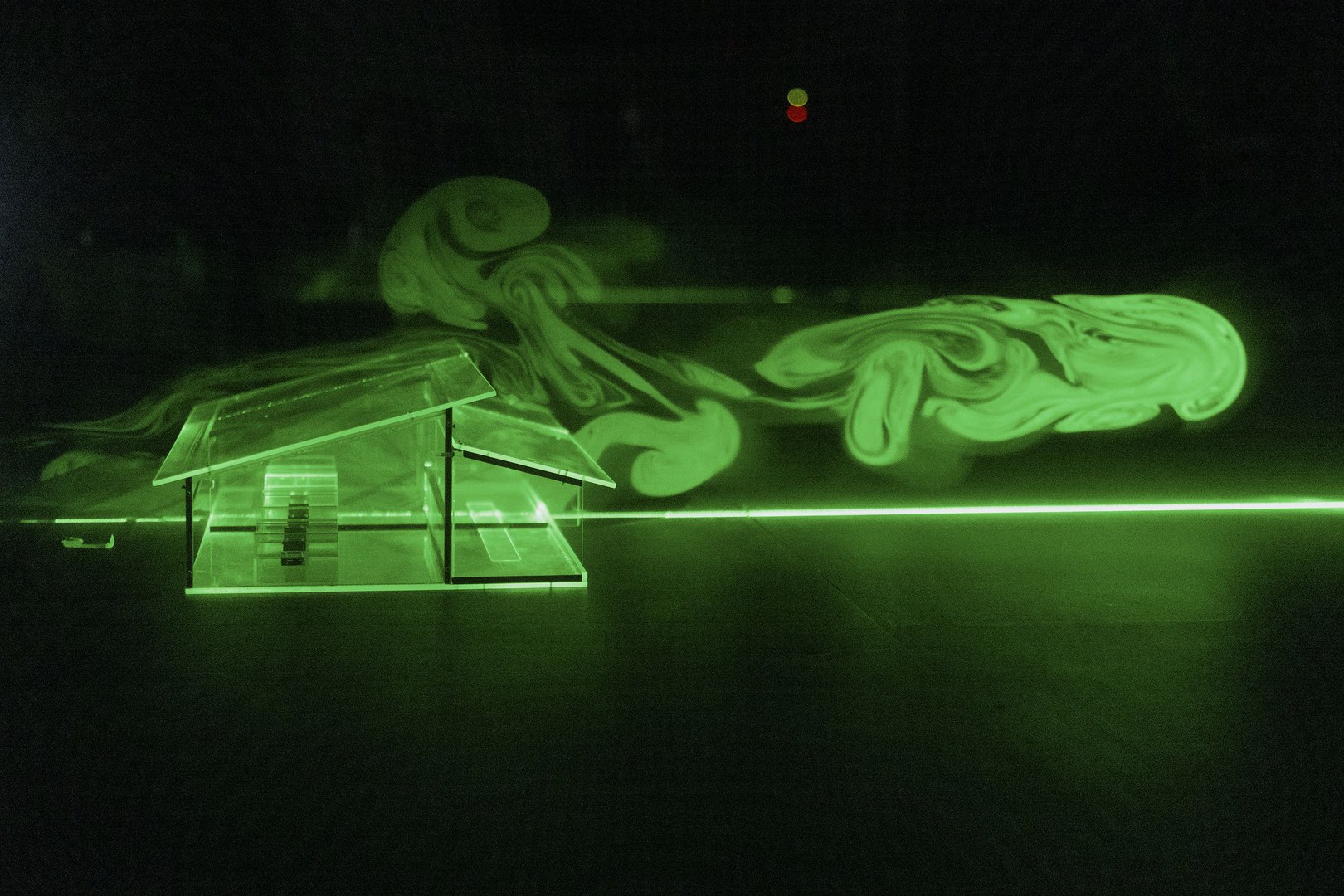

The newly approved joint project is hoping to change this. As well as devising new, cheaper ways to measure the gases being emitted, the partners are also planning to reduce the scope of the measurements without affecting the informative value of the results. To this end, they want to investigate which places where emissions are generated can be focused on and which can be ignored. Simulation software will also make predictions about the success of a particular measure in the future thanks not least to self-learning algorithms borrowed from artificial intelligence (AI) research.

The Federal Ministry of Food and Agriculture will be providing over €10,5 million in funding to the joint project, with an interim evaluation to be carried out after the first three. Nine institutions from across Germany are involved in the project. The University of Bonn will be receiving around €1.2 million, including almost €800,000 in the first three years leading up to the interim evaluation. The project is being coordinated by the Darmstadt-based Kuratorium für Technik und Bauwesen in der Landwirtschaft e. V.

“We’re delighted that our proposal was accepted,” explains Prof. Dr. Wolfgang Büscher. “A third of anthropogenic methane emissions worldwide comes from livestock farming, while ammonia accounts for as much as nearly 80 percent of emissions in Germany. Affordable, reliable measurement methods could help to reduce these levels and thus go a long way toward protecting the environment and mitigating climate change.”

To the press release of the University of Bonn:

https://www.uni-bonn.de/de/neues/129-2023 | 12.07.2023